|

If you remember the time when Montevallo or West Blocton

sidewalks looked like Sears on a Christmas Eve, then chances are you were around

when mining was king in Shelby County and the surrounding areas of the Cahaba

Coal Field.

To many it was "the gold old days," while to many

others it meant hard days of toil in the bowels of the earth for a dollar a day.

It was a time when the trains came through, making stops at just about every

mining camp or town between West Blocton and Birmingham.

But no matter what it meant, it was a time when coal made

the area, and the people lived like it. To merchants it meant Saturday sales

that couldn't be beat. To miners, it meant a Saturday when the mines could be

left behind and their dollars spent in booming Montevallo, West Blocton, or even

Birmingham. To the miners' families it meant a time when they could leave the

mining towns with funny names which surrounded Montevallo and West Blocton for

the "splendor" of the big town shops and stores.

All across Shelby County and parts of Bibb, coal was big

business. From around 1870 until the 1950's coal remained big business in and

around Montevallo. Coal was brought up from beneath the ground by the thousands

of tons. It was coming from one of the richest fields in the state and the

South, the Cahaba River Basin Fields. It was a high grade coal that could be

used both for heating and steel production.

It is thought that one of the greatest periods of the

coal boom in Shelby County and the surrounding area was between 1900 and 1929

when mining towns flourished all around the area. At one point it was estimated

that some 5,000 miners were in Montevallo area during the period just in the

towns of Aldrich, Dogwood, Marvel, and Boothton.

Many of those mining towns and the names of the mines

they worked in will be familiar with local residents. They started in the north

at Acton and stretched all the way down the Cahaba to below West Blocton at one

time. Their names were such things as Marvel, Garcy, Gurnee, Gurnee Junction,

Coalena, Piper, Blocton, West Blocton, Bell Ellen, Hill Creek, Red Eagle,

Mofitt, Aldrich, Dogwood, Old Maylene, New Maylene, Old Straven, New Straven,

Export, Boothton, Coalmont, Roebuck, Scratch Ankle, and many more.

The mines in these places made many men rich, while to

countless others it provided work. But it was hard work, and in many cases

dangerous work. This type of work, though, is said to get into a man's blood and

it's something that's hard to shake. Many old timers admit they would go back

into the mines tomorrow if they were still open and health permitted.

While the pay was low for the most part for the work,

there were benefits. Miners were provided low cost housing for themselves and

their families in the villages surrounding the mines. A fine example of this is

in Aldrich and Marvel, both mining towns long since without mines. Only the

miner's houses remain.

And the mining towns all had a company store, made famous

by Tennessee Ernie Ford's song "16 Tons." Goods were bought on credit and paid

off in labor according to one West Blocton miner of the time. But the store was

always there.

"You load sixteen tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt

Saint Peter don't you call me 'cause I can't go

I owe my soul to the company store"

And there was health care, maybe not always the finest,

provided by the company. Children in many towns went to schools and churches

built by thoughtful mine owners such as those which once graced Aldrich.

But probably most remembered by miners and others from

those times was Saturday in town. Movie houses flourished, stores stayed open

until 8:30 or 9:00 p.m. to accommodate the large crowds and money and good times

flowed.

Herman Stone, Montevallo businessman and one time miner

himself who was badly injured in a 1928 mine accident, recalls those times.

He said going into West Blocton on a Saturday was like

"you were going into old Dodge City, Kansas. It was wild."

Montevallo was much the same according to reports. But

those who wanted more than West Blocton or Montevallo, who were big rivals at

the time, could travel to Birmingham for the day. Trains left from most towns

such as Boothton in the morning for the Iron City, and returned at night full of

miners who had taken in the sights and thrills that Birmingham included.

But time took its toll. Gradually the mines began to die

out as they were worked out or priced out of competition. Many tried to operate

gopher hole mines -- operations with a wagon, a couple of mules, and their backs

-- but this faded out. These gopher mines reached their peak when the larger

mines were booming, but died along with the others.

As the mines died, so did the Saturday spirit for many.

There's one group who gathers each year at Boothton, near Montevallo, to

remember. They meet each year the first Sunday in October and have been doing so

since 1957 when the first group of 457 former residents of the area gathered.

The effort was started by Mrs. Herman Stone's mother, Mrs. Myrtle Terrell.

Somehow in their meetings each year they keep the spirit of what once was in the

area alive.

But for the most part mining is gone in the area. In its

place is strip mining in places where underground mining would be useless,

impossible, and too expensive. The most expansive stripping operations can be

found now near Boothton and Marvel.

What closed the mines? Some say it was Mine Union Boss

John L. Lewis who they say drove the price of operating mines out of reach for

most operators. Because of him, miners now draw no pay instead of high wages

they claim.

But there are countless miners who will argue this. He

was their saint, a tough many who raised wages from the lowly dollar a day to

livable scale. These people will tell you it wasn't Lewis, but rather the lack

of good coal and the price of it which drove many operators out of the business.

Throw in the fact rising water, other sources of energy, and more to get the

reasons. It was a combination of all of these things which added to the death of

a way of life for many.

But the future may be brighter. There is growing talk

that mining, the underground type, may be making a comeback soon. Already

experts from many companies have been taking core samples from deep depths in

the area to see if the rich saucer-like veins are still there. Experts are

saying there could be millions of tons of high grade coal still under the area,

and with new shaft designs and techniques, coupled with the rapidly rising value

of coal, mining could make a comeback.

There are many in the area who wish for it. Coal helped

to make Shelby County and the surrounding area what it is today. It could make

us even greater in the future.

The Aldrich Coal Mine Museum housed in the Company Store

of the former Montevallo Coal Mining Company,

and the beautiful

Farrington Hall, built by Mr. and Mrs. William Farrington Aldrich,

houses many Aldrich items from its past and an enormous number of pictures and

artifacts.

"Mine Explosion At Helena Takes Toll"

~ Heavy Loss of Life In Mine Disaster Last Week In

Shelby County ~

The following appeared in The Shelby County

Reporter dated Thursday, February 4, 1926.

An explosion that took the lives of 27 men, 11 white and

16 colored, occurred in the Mossboro mine of the Premier Coal Company near

Helena Friday afternoon about 4 o'clock. Sixty men were at work in the mine.

The explosion was caused, most of the survivors stated,

by an charge of black powder that blew backward and in the misfiring set off the

coal dust. It is said to have been very severe and most of the men were believed

to have been killed instantly.

The work of removing the bodies of the dead men required

practically all Friday night. The blast loosed a pond of water that flowed into

and filled the pit, making the work of the rescue all the more difficult. For

hours the crew worked in water waist deep among heaps of fallen stone and

twisted steel to find the badly mangled bodies of the dead men.

Several of the men, it is said, had been at work in the

mine only a week. Some of them were in the Overton mine on December 11 when an

explosion took the lives of 53 men.

The names of the unfortunate men are:

White

James Adams, Robert Ball, Pat Burke, William Carrick, Glenn Duncan,

Henry Gold, W.J. Harrison, M.J. Holloway,

Doyle Lambert, Joe Mayner and

Henry Oakes.

Negroes

W.M. Odum, Hassey Harris, Will Johnson, Henry Peterson, Enoch Woodwon,

W.H. Segress.

Those still in the mine, but who are believed to be dead are:

Colored

Amberson Grigley, More Coillins, Eli Treadwell, Willie Temple, Cliff

Gibson, Willie Fitts, Primus Hendersib, Rodger Williams, Sam Hawkins.

Those who escaped are:

Whites

J.D. Lowery, J.B. Lowery, a son Edgar Lowery, Zach Chapman, Lonnie

Chapman, Lloyd Robertson, B.D. Gold, George Zimmerman.

Negroes

Will Simmons, Jess Chestnut, Stanley Maddox, Walter Pearce, Archie

Jackson, Percy Pearce, Scott Saulders, Fletcher Anderson, Will Lambert,

Millard Garner, G.G. Garner.

"First Coal Was Mined In State Over A Century Ago"

The following appeared in The Shelby County

Reporter dated Thursday, December 18, 1930

Alabama's coal industry celebrates this month, its

one-hundredth anniversary.

In 1830 -- a full century ago -- when Chickasaws,

Choctaws, Cherokees and Creeks still roamed through Alabama's then virgin

wilderness -- eleven years before the State's admission to the Union --

Alabama's first coal was mined commercially, near what is now Tuscaloosa and was

floated down to Mobile. It is probable that the passage of this boat aroused but

scant interest among Alabama's pioneer settlers. Little could they have

realized, as they stood upon the banks of the Warrior and watched the cargo

drift by, that they were witnessing a significant event in Alabama history --

the birth of an industry which was destined to play, perhaps the most vital role

of any single industry in Alabama's economics progress during the ensuing

century. Yet time has proved that this was to be true.

Coal Shapes State Progress

Commemorating the centennial of Alabama's coal industry,

leaders have released some interesting data which throws a new light upon the

part which coal has played in shaping Alabama's destiny. Early chronicles of

coal producing companies now operating in the State have qualities of a peculiar

historic interest -- roots which reach deep, almost as their mines, into the

bed-rock and sub-strata of Alabama history and legend. Early annals of producing

companies reveal, for instance, that Alabama coal has had a close relationship

with the United States Army and Navy, the Confederate States Army and Navy, the

United States Senate and House of Representatives, the development of Alabama's

railroad system, the growth of many Alabama cities, the building of scores of

varied industries and businesses, which have in turn contributed their share to

Alabama's steady forward march throughout a century of amazing progress.

564,000,000 Tons Mined

Records show that since the first coal was floated down

the Warrior in 1830, 564,000,000 tons have been mined in the State. From 1830

until 1870 the tonnage has been estimated, as no official records are available

for these first forty years. The first available statistics reveal that in 1870,

13,200 tons were produced; in 1880, 380,000 tons; in 1890, 4,090,409 tons; in

1900, 8,273,262 tons; in 1910, 16,139,228 tons; in 1920, 17,391,437 tons and in

1926 the maximum productions of 21,508,812 tons. Last year the tonnage dropped,

because of competition from outside fuels, to 18,415,914 tons.

Removal of this treasure, which Nature stored in

Alabama's hills a million years or more ago, has furnished steady jobs to many

thousand Alabama workers. It is estimated that to mine the coal which Alabama

has produced during the last century, has required about 188,000,000 man-days

work.

$750,000,000 in Wages

Wages paid to workers in the coal industry during the

past century are estimated to have aggregated well over three quarters of a

billion dollars. In peak years, Alabama coal mines have provided around seven

million man-days work a year for thirty thousand employee, and an annual payroll

has percolated throughout the State, penetrating every section. Investigation

shows that it is spent by wage earners and salaried employees of the industry

for merchandise, food products, transportation, amusements and insurance or is

invested in securities and savings banks. Seventy cents out of every dollar

received by the producer goes to labor. A goodly part of this is spent for farm

produce, as shown by the fact that coal mining companies in the Birmingham

district alone, buy annually in good years around five million dollars worth of

products raised on Alabama farms, orchards and truck gardens.

Supplies Huge Freight Revenue

Closely paralleling the development of Alabama's coal

industry has been that of Alabama railroads. Officials of the leading roads have

stated that the present splendid railroad system, which networks the State,

could not have been built except for the coal tonnage, which normally provides

about 25 per cent of the total freight revenue of all the lines in the State.

This does not include freight revenue from hauling mine supplies and machinery

nor revenue from the handling of coal by-products. To haul the 564,000,000 tons

of coal mined in Alabama during the past century, has required use of some

11,280,000 fifty-ton freight cars, and furnished regular employment to many

thousand trainmen, enginemen and other railroad operatives who, in their turn,

have spent their wages in the State.

Parent of Many Industries

Out of Alabama's coal Industry, many other industries

have been born -- industries which feed on coal and industries which use the

many valuable derivatives of' coal. Alabama's great steel industry, pipe

industry, chemical industry -- to name a few of many hundred -- could not have

sprung into existence except for the availability of Alabama's huge coal

deposits which are estimated to approximate eighty-seven and a half billion

tons, enough to last for 2,500 years or longer. Without coal mining, it is

easily conceivable that Alabama in the year 1930, would have shown but little

industrial development over 1830. For, without coal mining, Alabama ores could

never have been economically turned into merchantable products. Without coal

mining Alabama's present railroad system would not have been built. Without coal

mining Alabama would not rank today, fourth in the production of by-products

derived from converting coal into coke, and without coal mining there would be

no nearby markets for the products of the forests and the farms of the State.

These are a few of the reasons why Alabama places such a

high value on her coal mining industry and will join this month in celebration

of its one hundredth birthday.

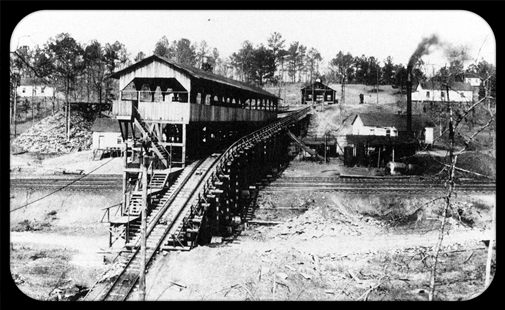

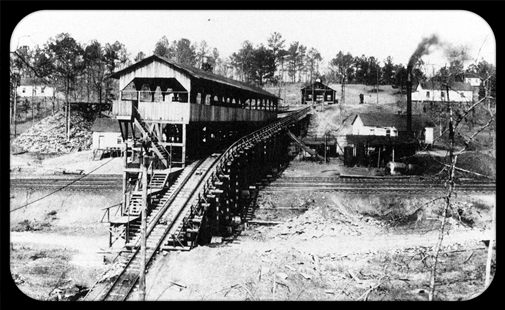

Acton Coal Mine #4

Acton Coal Mine #4

|